Tom Black Jack Ketchum Death

Who was the Wild Bunch? What crimes can be attributed to the gang? And who participated in those crimes? These questions defy simple answers.

- Tallulah Bankhead

- Tom Black Jack Ketchum Death Hoax

- Tom Black Jack Ketchum Death Pictures

- Tom Black Jack Ketchum Death Row

- Tom Black Jack Ketchum Death Notices

- Two years later, on July 11, 1899, they held up the same train, but Tom Ketchum wasn’t along. His brother Sam, however, got shot in the attempted robbery and was subsequently captured, but died two weeks later in prison. On August 6, 1899, Ketchum—who knew nothing of Sam’s botched attempt—decided to rob the same train.

- Why You Should Pay a Visit: Along with his brother Sam, Thomas Edward Ketchum, better known as Black Jack, led the train-robbing Ketchum Gang. During an 1899 train robbery that he tried to pull off on his own, Black Jack got shot in the arm, which had to be amputated.

Take the last: Who participated in the gang’s crimes? The bandits almost always escaped, which makes identifying them difficult.

Tom was given the sobriquet “Black Jack” after southern Arizona highwayman Will “Black Jack” Christian, who was killed in April 1897, even though the pair had only met once. Tom later tried to disown the “Black Jack” label because he felt that some of Christian’s crimes would be blamed on his gang.

Eyewitnesses are unreliable at best, and they are especially dodgy regarding masked perpetrators. Witnesses to Wild Bunch crimes disagreed on descriptions, even on how many bandits were involved. Those indicted were usually acquitted. So how can we, a century later, determine the truth? We can only try.

On June 24, 1889, Butch Cassidy, Matt Warner and Tom McCarty (abetted by others, perhaps including Bill Madden and Butch’s brother, Dan Parker) robbed the San Miguel Valley Bank in Telluride, Colorado, of around $20,000. Considering that trio as the root of the Wild Bunch, we can fold in later crimes in which they participated.

Tom McCarty and Matt Warner along with Tom’s brothers Bill and George, his nephew Fred, his brother-in-law Hank Vaughan, and George’s wife Nellie staged about 10 holdups in Oregon, Washington and Colorado between 1890 and 1893. The outlaws’ tastes were catholic: They hit trains, banks, casinos and stores. The gang dissolved after Fred and Bill died during an 1893 attempt on the Farmers and Merchants Bank in Delta, Colorado.

The Rocky Mountain branch of the Wild Bunch made an inauspicious start on November 29, 1892, near Malta, Montana, when three men—probably the Sundance Kid, Harry Bass and Bill Madden—held up the Great Northern No. 32 and netted less than $100. Bass and Madden were caught and implicated Sundance, who had escaped.

Butch Cassidy’s outlaw career resumed in 1896, after a two-year prison term for horse theft. On August 13, he, Elzy Lay and Bub Meeks robbed Idaho’s Bank of Montpelier of $7,165. The money went to attorneys defending Matt Warner for murder. On April 21, 1897, Butch, Lay and perhaps Meeks and Joe Walker stole a $9,860 mine payroll in Castle Gate, Utah.

On June 28, 1897, six bandits flubbed a holdup of the Butte County Bank in Belle Fourche, South Dakota. Tom O’Day was caught hiding in a saloon privy. His cohorts included Walt Punteney, George “Flat Nose” Currie, Harvey Logan (making his debut in the Wild Bunch) and Sundance. Butch may have participated, but it’s doubtful. The bungling bandits got $97. O’Day was tried and acquitted; Punteney was arrested, but the charges were dropped.

Butch’s reputation outpaced his criminal record. In a story headlined “King of the Bandits,” a Chicago daily declared in early 1898 that “Butch Cassidy is a bad man.” Not just any bad man, but “the worst man” in Utah, Colorado, Idaho and Wyoming, the leader of a gang of 500 outlaws “subdivided into five bands.”

On July 14 that year, a trio of bandits, said to have been Sundance, Logan and Currie (though they were never identified), held up the Southern Pacific No. 1 near Humboldt, Nevada, escaping with $450. Two other men were tried for the holdup and acquitted.

The Humboldt threesome struck again on April 3, 1899, robbing a saloon in Elko, Nevada, of several hundred dollars. The Wild Bunch holding up saloons? Maybe not. (Unsolved crimes are often attributed to famous outlaws.) Three local cowboys were tried for the robbery and acquitted.

Meanwhile, other outlaws were roaming the Southwest. Three Texas delinquents, Tom “Black Jack” Ketchum, Dave Atkins and Will Carver, held up a Southern Pacific train near Lozier, Texas, on May 14, 1897, taking upwards of $42,000. Reinforced by Tom’s brother, Sam, and possibly Bruce “Red” Weaver, they robbed the Gulf, Colorado & Santa Fe No. 1 on September 3, 1897, of several thousand dollars. Weaver was later tried for the crime and acquitted.

Success bred carelessness. On December 9, 1897, five bandits, probably the Ketchum brothers, Carver, Atkins and Edward H. Cullen, attempted to rob the Southern Pacific No. 20 near Stein’s Pass, New Mexico, but met a fusillade from armed guards. Cullen was killed; the other four, though wounded, escaped. Unchastened, four men—probably the Ketchum brothers and perhaps Carver and Ben Kilpatrick—robbed the Texas Pacific No. 3 at Mustang Creek, Texas, on July 1, 1898, grabbing between $1,000 and $50,000 in cash. (Victims were not forthcoming about how much was stolen. Sometimes employees pocketed overlooked money and included it in the amount said to have been taken by the bandits. At other times, initial accounts lowballed the sums, and the truth came out decades later.)

Elzy Lay joined the gang just in time for its train-robbing blitz to come to a bloody halt. On July 11, 1899, Sam Ketchum, Lay and Carver overpowered the crew of the Colorado & Southern No. 1 and galloped off with some $30,000. (Weaver, thought to have been standing guard nearby, separated from the others.) After the holdup, the three principals were surprised by a posse. When the dust settled, one posse member was dead and two were wounded, one mortally; Sam Ketchum was mortally wounded; Lay was wounded and later captured; and Carver escaped. (Some say the third bandit was Harvey Logan, not Carver.)

Tom Ketchum, meanwhile, picked an inauspicious moment to launch a solo career. On August 16, 1899, he attempted holding up the Colorado & Southern No. 1 near Folsom, New Mexico, but was shot, captured, tried, convicted and hanged.

These calamities should have been a lesson to Carver and Kilpatrick, but they merely moved north and joined the Wild Bunch proper.

The first crime that consolidated what was left of the various gangs was the June 2, 1899, robbery of the Union Pacific Overland Flyer No. 1 near Wilcox, Wyoming. This holdup, which yielded between $3,400 and $50,000, made the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang nationally famous. “They were lawless men who have lived long in the crags and become like eagles,” averred the New York Herald. Yet we can’t place Butch or Sundance at the scene with any precision. Witnesses reported six masked men; most historians count George Currie, Harvey Logan, his brother Lonnie Logan and their cousin Bob Lee among them.

The lawless eagles swept down again on August 29, 1900, robbing the Union Pacific Overland Flyer No. 3 near Tipton, Wyoming, of between $55.40 (the initial account) and $55,000 (a later report). The five bandits included Butch and probably Sundance and Harvey Logan. Also suspected were Ben Kilpatrick, Tom Welch and Billy Rose. Tipton was the first crime in which Butch and Sundance are generally agreed to have teamed up. They were just six months from fleeing the country.

Three weeks later, on September 19, three or four bandits struck the First National Bank in Winnemucca, Nevada, collecting between $32 and $40,000. Sundance, Carver and Logan are thought to have participated, but some suspected local miscreants, and others called it an inside job. The bank’s head cashier, George Nixon, at various times agreed and disagreed that Butch was present. A few years later, a newspaper recounted a conversation in which Sundance supposedly disclosed that he, Butch and Carver were responsible. Stories that the bandits had camped near Winnemucca as early as September 9, however, have prompted researchers to question whether Butch could have been at both Tipton and Winnemucca, 600 miles apart.

Butch and Sundance left for Argentina in February 1901. Today popularly considered the leaders of the Wild Bunch, they had teamed up on only two or three robberies. As crime sprees go, it was not much of a run. Their colleagues sputtered on, but within a couple of years most were dead or in jail.

On July 3, 1901, what was left of the gang on North American soil attacked the Great Northern Coast Flyer No. 3 near Wagner, Montana, fleeing with about $40,000. There were four to six bandits, including Harvey Logan, Ben Kilpatrick and O.C. Hanks. Kilpatrick and Logan went to prison for passing bank notes from the holdup, and Hanks died the next year in a confrontation with authorities in Texas.

Logan, who had escaped from jail in 1903, rounded up two friends, probably from Ketchum territory, for what would be his farewell appearance, the botched holdup of the Denver & Rio Grande near Parachute, Colorado, on June 7, 1904. Wounded and cornered, Logan committed suicide. The list of possible accomplices is long, but George Kilpatrick (Ben’s brother) and Dan Sheffield are high on it. George is thought to have been mortally wounded, although his body was never found.

The northern hemisphere’s Wild Bunch was kaput, except for one footnote. Ben Kilpatrick, released from prison in 1911, joined former cellmate Ole Beck to rob the Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio No. 9 near Sanderson, Texas, on March 13, 1912. Quick-witted Wells Fargo messenger David Trousdale fatally bludgeoned Kilpatrick with an ice mallet, borrowed his rifle, and dropped Beck.

So, what was the Wild Bunch? Between the late 1880s and early 1900s, there were several gangs, comprising several dozen outlaws, who are part of the Wild Bunch story. The McCarty-Warner and Ketchum Gangs had more coherence than the Rocky Mountain Wild Bunch, perhaps because they were family based. All the bandits put together committed or attempted more than two dozen holdups. They probably didn’t do some they’ve been blamed for, and they probably pulled others they’ve never been accused of.

Of the approximately 20 outlaws who can be counted in the Rocky Mountain Wild Bunch during its heyday, the 1896-1901 Montpelier to Wagner era, few participated in crimes together more than a couple of times, and the gang’s holdups in that period numbered a scant five to seven. Butch and Sundance—surprisingly, given their later iconic status as a joined-at-the-holster outlaw duo—teamed up in the United States no more than three times. If they hadn’t gone to South America and died together, the 1969 movie would never have been made, nor this article written.

Daniel Buck and Anne Meadows are contributing editors of South American Explorer, and Anne wrote Digging Up Butch & Sundance (1996). A bibliography of their works on the Wild Bunch can be found at: http://ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/danne/

Photo Gallery

Related Posts

Tallulah Bankhead

L.G. Davis was the sheriff of Carbon County, WY. The Wild Bunch had been on…

By the early 1900s, the law was closing in and Butch Cassidy was beginning to…

George Scarborough was a tough and deadly lawman—until he ran into members of the Wild…

Buildings on the south side of Folsom, New Mexico, by Kathy Weiser-Alexander

Tom Black Jack Ketchum Death Hoax

Situated on the Dry Cimarron Scenic Byway, Folsom is a semi-ghost town sitting at the junction of New Mexico Highways 325 and 456 in Union County, New Mexico.

When we traveled this route last time the “Dry Cimarron” River, actually was flowing with water. By Kathy Weiser-Alexander.

Lying in the wide Cimarron River Valley and surrounded by buttes, mesas, and old volcanic cones, this area was long utilized as hunting grounds for the Comanche, Ute, and Jicarilla ApacheIndian tribes.

The first white settlement in the area was Madison, settled in 1862 and named for its founder, Madison Emery who built a cabin at the site. As more families arrived, homes, stores, and other businesses sprang up and Emery also erected a rough hotel. In its early days, Madison was the nearest settlement to the “Robbers’ Roost” just north of Kenton, Oklahoma, which was home to a band of outlaws led by Captain William Coe in the late 1860s. When the outlaws sensed a raid on their “Roost”, they would often hide out in Madison. Coe was eventually caught in Madison by the US Cavalry with the help of Emery Madison’s wife and step-son. He was taken to Pueblo, Colorado to await trial, but was lynched by a group of vigilantes before he had a chance. After Coe was captured and killed, the rest of the gang must have scattered because they were never heard from again.

In 1877 a post office was established at Madison. The coming of the Colorado and Southern Railroad in 1887 killed the settlement because the line bypassed the town. Madison’s post office closed in 1888. Today there is little physical evidence that it ever existed except foundations of an old grist mill.

The Colorado and Southern Railroad cut across the northeast corner of New Mexico in the late 1880s and many of Madison’s former citizens moved to the new town that sprang up about eight miles to the northeast. The railroad was the only one in the northeast part of the state until 1901. The community was first called Ragtown because the shelters and business establishments were all tents. When the bride-elect of President Grover Cleveland, Francis Folsom, stepped off the train to explore the little town during a whistle-stop, the townspeople were smitten by her charms and the town was named for her. Folsom gained its post office in 1888 after Madison’s closed.

Tom Black Jack Ketchum Death Pictures

One of the first citizens in Folsom was W. A. Thompson who was the proprietor of the Gem Saloon and deputy sheriff. Arriving from Missouri, where he had been charged with murder, he quickly racked up a lurid record in Folsom. He was said to have shot and killed a friend because he visited another saloon. On another occasion, enraged at a boy for taunting him, Thompson chased the boy with a six-shooter and when he failed to catch him, turned his guns on a fellow officer and a customer emerging from a store, killing one of them. Though Thompson was captured and tried in Clayton, New Mexico he was acquitted and went to Oklahoma, where he was said to have killed another man.

Late in the 1880s, two Dallas investors put together nearly $50,000 to build a mineral springs resort just east of town. Their plans included a hotel on the edge of a canyon and the building of a dam to create a small lake for fishing and boating. When Hotel Capulin was almost complete, the investors got into a dispute and dropped the project completely. Afterward, the investors never returned and the magnificent hotel was abandoned. Locals then used the building for parties, vagrants moved in, and bits and pieces were taken for the structure for other building purposes. The flood of 1908 finally washed away what was left.

Old homestead in Folsom, New Mexico by Kathy Weiser-Alexander.

The town prospered in its early years with the largest stockyards west of Fort Worth, Texas and a number of land speculators working in the area. Numerous homesteaders moved in and established farms and ranches. The area cowboys and farmers relied on the town for supplies and a taste of civilization. The town boomed with as many as 1,000 people in the area and the town responded with hotels, restaurants, supply stores, two mercantile stores, doctors, newspapers, and three saloons. Three school houses were built after the first two burned.

On September 3, 1897, the Ketchum Gang held up the train near Folsom. Sam Ketchum and several other men held up the train at the same site on July 11, 1899. A posse caught up with them in Turkey Canyon and a fight ensued in which Sheriff Edward Farr of Walsenburg, Colorado was killed. Sam Ketchum and Elza Lay were wounded as were five of the eight members of the posse. Henry M. Love, another posse member died of his wounds four days later. Sam was taken to the penitentiary at Santa Fe where he died of his wound. Elza Lay, who had made his escape, was later sent to the New Mexico Territorial prison

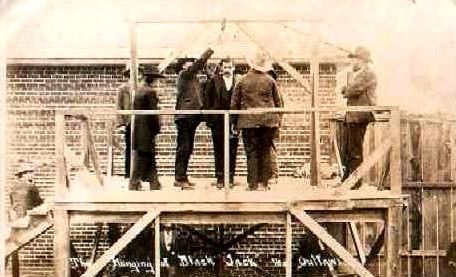

On August 16, 1899, Tom “Black Jack” Ketchum tried to hold up the train at the same place by himself and was seriously wounded by the conductor, Frank E. Harrington. Ketchum was picked up beside the tracks the next day. His arm was amputated on September 9 while he was awaiting trial. He was hanged on April 26, 1901, at Clayton, New Mexico.

By the early 1900s, the area was still doing well but the town’s population had fallen as many of the homesteaders found that the area proved unsuitable for farming

In 1908 the town had a new telephone switchboard which was operated by Sarah J. Rooke in her home on the edge of town. Sarah was an older unmarried woman. On August 27, 1908, Sarah answered her buzzer to hear a voice shouting that a flash flood was racing down the river and would strike the town within minutes. Sarah rang one phone after another warning people to get out of town before the water hit. She was still sitting at her switchboard when her own house was swept from its foundations and her body was later found eight miles below the town. Most of the town’s buildings were carried away and 18 people, including Sarah Rooke, drowned. She was buried at the Folsom Cemetery south of town. A granite monument with a plaque was erected by her fellow workers. This was not the first flood in the town, as a report in the Folsom Metropolitan reported on another damaging incident in August of 1890.

Tom Black Jack Ketchum Death Row

A flash flood in 1908 exposed this archaeological site near Folsom, New Mexico. The site was named for the nearby town of Folsom.

Shortly after the flood if 1908, George McJunkin, an African American cowboy, amateur archaeologist and historian, who was working as a foreman on the Thomas Owens Pitchfork Ranch, discovered remains of a giant prehistoric bison in Wild Horse Arroyo about eight miles west of Folsom. Though it would be years before the site was excavated, when it finally was, archaeologists found 32 skeletons and at least 26 spear points, now known as “Folsom Points”. This discovery changed the thinking in the world of archaeology, pushing the presence of man in North America back by at least 5,000 years to 12,000 years. The site was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1961.

Slowly, most of the homesteaders gave up as the weather turned drier. The remaining farmers accumulated the abandoned land into larger plots. However, as the area continued to suffer from drought, most of the farming holdouts gave up as well. Cattle and sheep ranchers bought up the farmlands that eventually returned to pasture.

Tom Black Jack Ketchum Death Notices

A high school operated briefly in Folsom, but it only graduated three students in 1931. Folsom’s elementary school closed in 1958, at which time the students were transferred to Des Moines, New Mexico. The school still stands and is used today for community events. By 1960, Folsom was called home to 142 people. The Doherty General Merchandise Store, built in 1896, stayed open until 1959.

Now a semi-ghost town, Folsom is a pleasant ranching community, called home to about 60 people and several historic buildings. The old 1888 railroad station was moved from the right-of-way around 1970 and is now used as a storage building and next to it, on the corner is the old Texaco gas station which was built sometime before 1946. Across the street is the Doherty Mercantile building, which became the Folsom Museum in 1966. The abandoned stone two-story Folsom Hotel still stands on the south side of Main Street along with several false-front stores.

On the north side of Main Street, is an active post office. St. Joseph’s Church continues to provide services at 118 N. 2nd Street and a cemetery is situated east of the church.

Folsom is located 36 miles east of Raton on New Mexico Highway 72.

The Capulin Volcano National Monument, rising to an elevation of 8,182 feet, is located seven miles southwest of Folsom on New Mexico Highway 325.

The Dry Cimarron Scenic Byway continues north from Folsom on New Mexico Highway 456.

Folsom Falls, New Mexico, courtesy Wikipedia.

About 3.5 miles northwest of Folsom, is the site of Folsom Falls, a natural spring-fed waterfall, which long served as a favorite fishing hole and picnic grounds for area residents. Unfortunately, it sits on private land behind a gate and the public is no longer allowed to visit today.

About eight miles north of Folsom, Highway 456 intersects with Highway 551. North on 551 is Toll-Gate Canyon where Charles Goodnight trailed many herds of cattle from Texas to Wyoming from 1866 to 1869. Between 1871 and 1873, Bazil Metcalf constructed a toll road from the Dry Cimarron through Tollgate Gap, providing one of the few reliable wagon roads between Colorado and New Mexico. This road remained an important commercial route until the Colorado and Southern Railway came through in the 1880s.

© Kathy Weiser-Alexander, updated March 2020.

Also See:

Sources:

Folsom Village

Miller, Joseph; New Mexico – A Guide To The Colorful State, Arkose Press, 2015

Varney, Philip; New Mexico’s Best Ghost Towns: A Practical Guide; University of New Mexico Press, 1987